-

Santa Ana creates emergency fund for families harmed by ICE raids - 3 hours ago

-

The Winners and Losers of Trump’s Big Bill, and a ‘60 Minutes’ Settlement - 1 day ago

-

California Rolls Back Its Landmark Environmental Law - July 1, 2025

-

Teen Mt. Whitney hiker who walked off 120-foot cliff in delirium makes slow recovery, family says - June 30, 2025

-

Thom Tillis, Republican Senator, Won’t Seek Re-election Amid Trump’s Primary Threats - June 29, 2025

-

Better Half - June 28, 2025

-

Flaw in Edison equipment in Sylmar sparked major wildfires, lawyers say - June 28, 2025

-

‘F1’ Movie Finishes With $10M in Early Showings Ahead of Opening Weekend - June 28, 2025

-

Sauce Gardner Opens Up On Ice Spice Relationship, LeBron With The Assist! - June 28, 2025

-

Four Astronauts Lift Off on Axiom Mission to the I.S.S. - June 25, 2025

The Man Put On Trial For Killing JFK Deserves an Apology

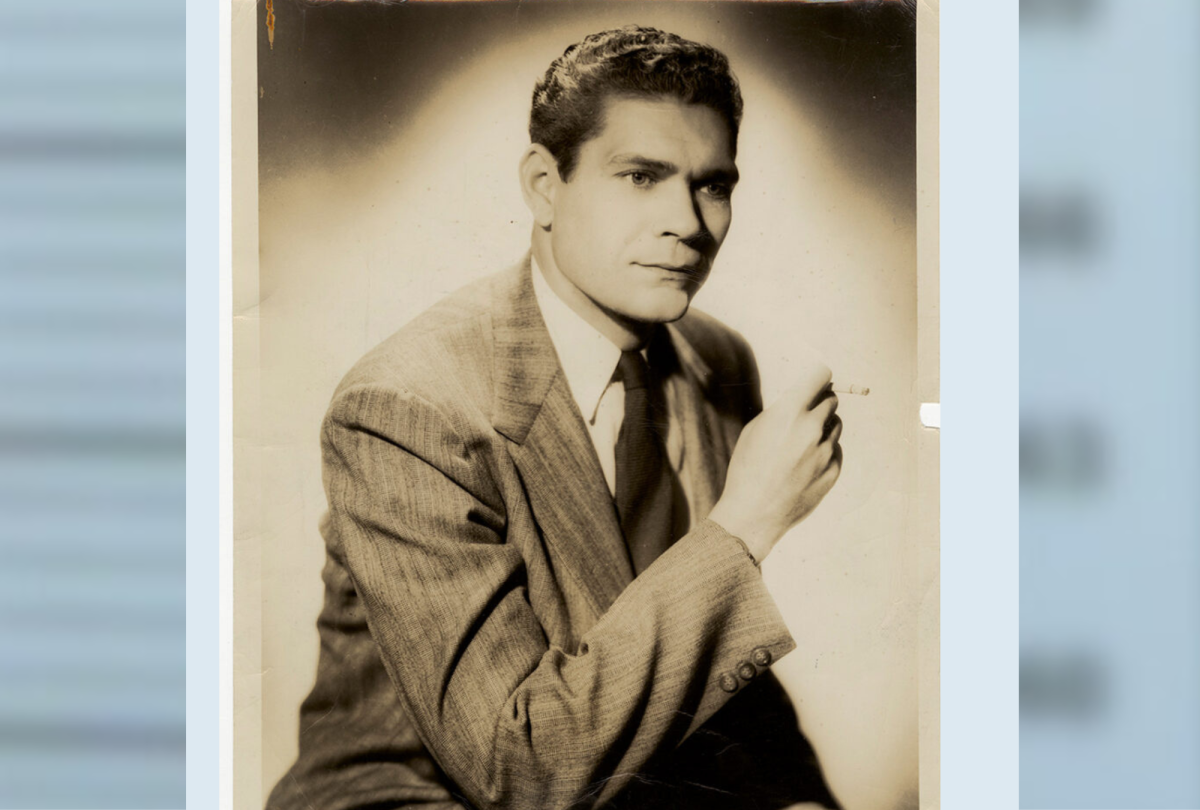

Clay Shaw was a gay New Orleans businessman who had a passion for restoring buildings in the city’s old quarter. A plaque on the city’s Governor Nichols Street, placed after his death in 1974, honors his restoration of The Spanish Stables and nine other buildings, as well as his role in creating the International Trade Mart and the French Market.

“Clay Shaw was a patron of the humanities who lived his life with the utmost grace,” the plaque reads.

Shaw is also remembered for much darker reasons: he is the only person ever to go on trial for the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, which occurred in Dallas on November 22, 1963—60 years ago next Wednesday.

Shaw spent the rest of his life proclaiming his innocence and telling reporters that he was the victim of an over-zealous New Orleans District Attorney named Jim Garrison.

NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION

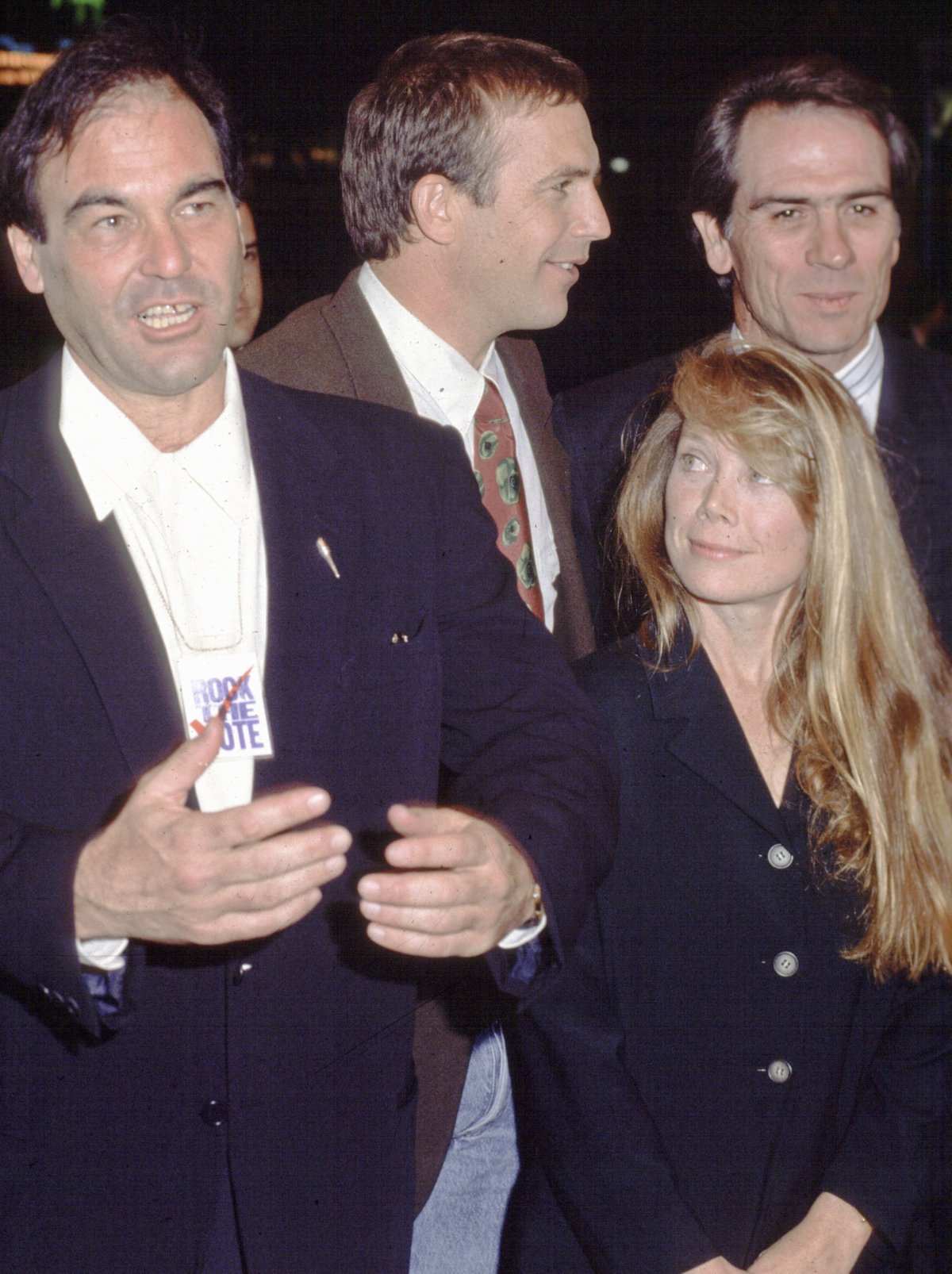

Garrison is the subject of Oliver Stone’s 1991 biopic, JFK, in which Kevin Coster’s Garrison is portrayed as an honest, diligent, family man fighting for justice and Tommy Lee Jones’ Clay Shaw is the conniving and ruthless head of a conservative, gay ring that was being used by U.S. generals in a bid to kill Kennedy and thereby escalate the conflict in Vietnam.

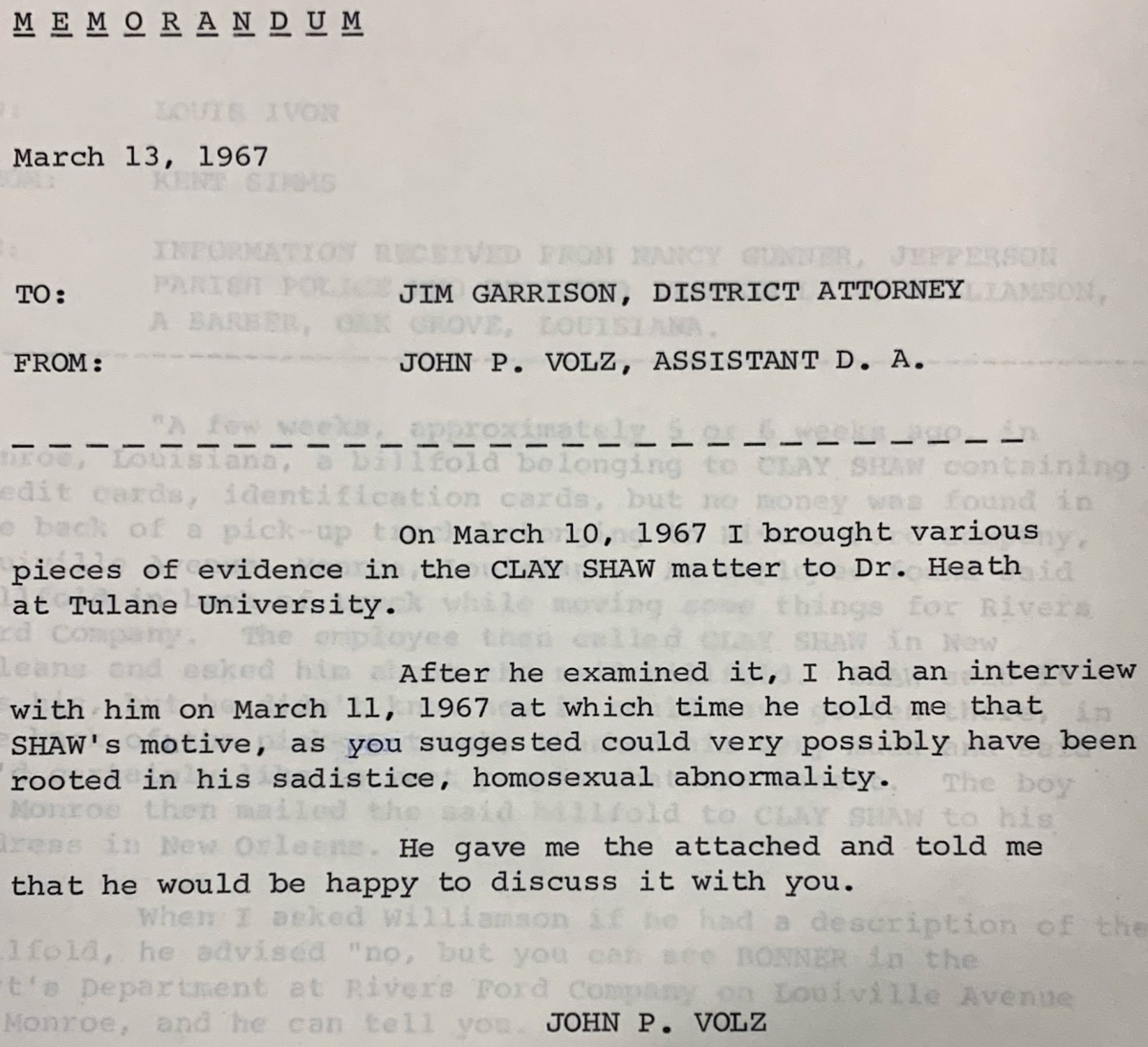

Garrison and his team focused on Shaw’s homosexuality and even consulted with a doctor on how Shaw’s homosexuality may have influenced his decision to kill the president.

A memo sent by John Volz, the assistant New Orleans District Attorney, to Garrison on March 13, 1967 reads: “On March 10, 1967, I brought various pieces of evidence in the CLAY SHAW matter to Dr. Heath at Tulane University.”

“After he examined it, I had an interview with him on March 11, 1967 at which time he told me that SHAW’S motive, as you suggested could very possibly have been rooted in his [sadistic], homosexual abnormality.”

Fred Litwin

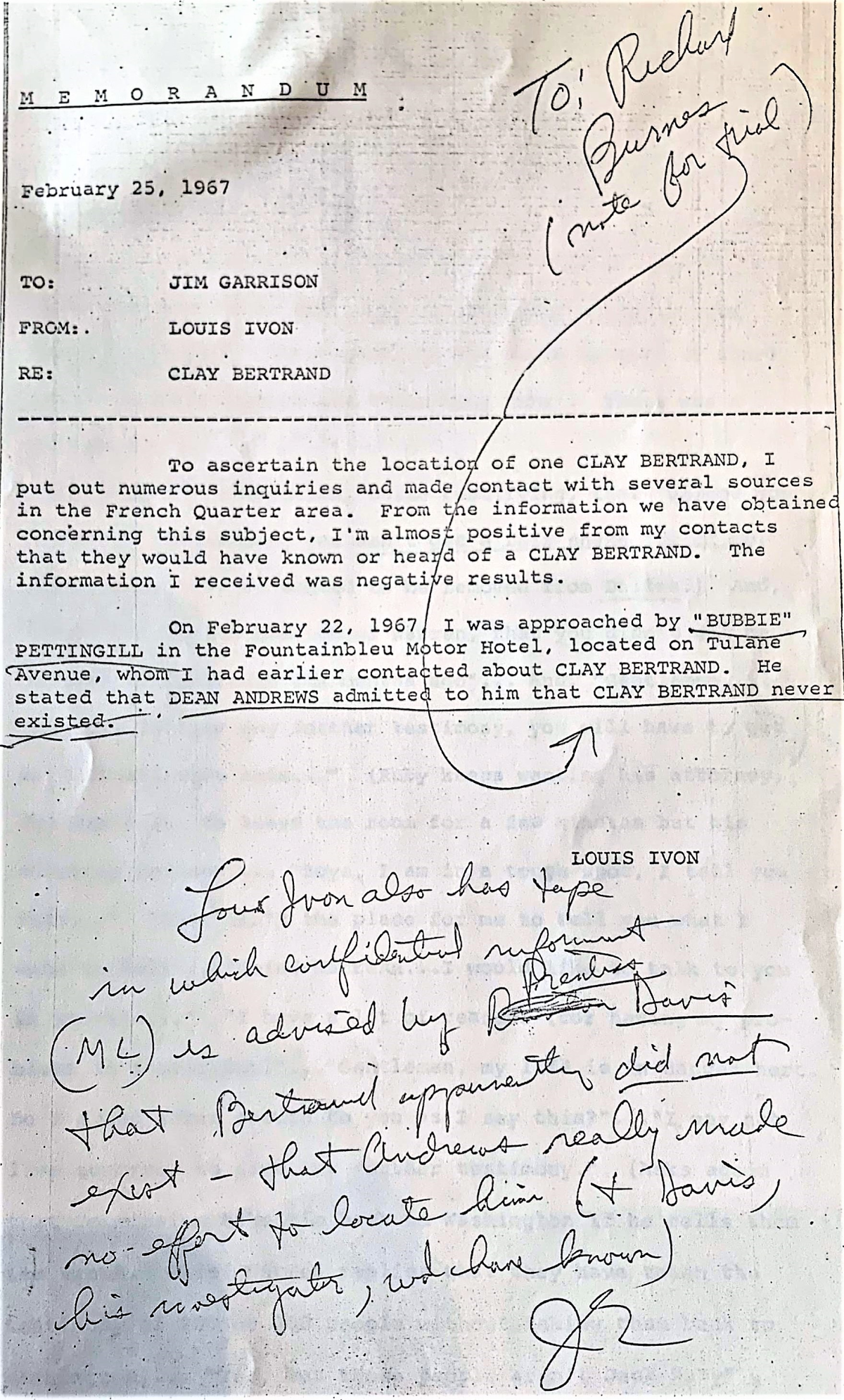

Garrison put Shaw on trial in front of the world’s media in 1969. Much of the evidence rested on Shaw being the true identity of a New Orleans conspirator named Clay Bertrand, despite a memo sent to Garrison by one of his investigators to notify him that their confidential source, a lawyer, had admitted that Bertrand had never existed.

The investigator, Louis Ivon, had sent Garrison a memo on February 25, 1967, informing Garrison that Ivon had made “numerous inquiries in the French quarter” but nobody knew of Bertrand, despite Ivon being “almost positive” that his contacts would know of Bertrand if he ever really existed.

The memo goes on to explain that Ivon went to the Fontainbleu Motor Hotel to meet one contact, Bubbie Pettingill, whom he had earlier asked about Bertrand.

Pettingill told Ivon that “Dean Andrews admitted to him that Clay Bertrand never existed,” the memo states.

Fred Litwin

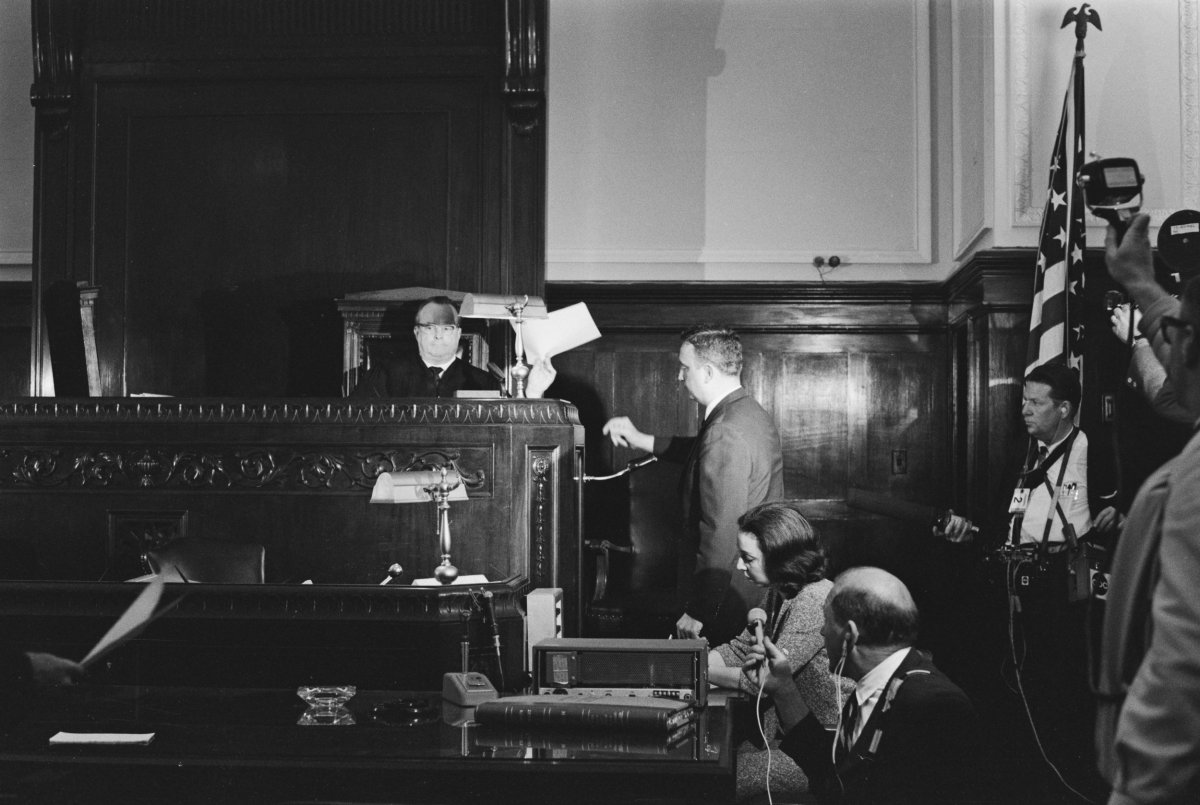

During the trial, Garrison referenced a memo in which Clay’s homosexuality was discussed, thereby outing him at a time when homosexuality was still illegal.

As Garrison’s case floundered in unsubstantiated conspiracy, he was heavily criticized in the media for the lack of meaningful evidence. Newsweek’s Hugh Aynesworth wrote: “If only no one were living through it—and standing trial for it—the case against Shaw would be a merry kind of parody of conspiracy theories, a can-you-top-this of arbitrarily conjoined improbabilities.”

Bob Simmons/Getty Images

Aynesworth said the trial had shown that “Clay Bertrand” was nothing more than something “dreamed up by a strange New Orleans lawyer named Dean Andrews.”

“Mr Garrison went on insisting that Shaw was Bertrand even after Mr Andrews admitted he had invented Bertrand and refused to identify Shaw as Bertrand,” Aynesworth added.

“Mr Garrison was hunting headlines and making up an assassination conspiracy as he went along. That still does not explain why he put the finger on Clay Shaw, a prosperous man-about-town, a witty and welcome bachelor dinner guest in the fashionable homes of the Garden District, and former managing director of the New Orleans Trade Mart.”

Getty Images/Bob Simmons

The jury didn’t believe Garrison and acquitted Shaw after less than an hour of deliberations. Garrison ordered Shaw re-arrested and charged with perjury three days after the trial ended.

Shaw granted several TV and newspaper interviews in which he said he would sue Garrison for vindictive prosecution and in 1972 a federal court issued a strongly-worded decision barring Garrison’s office from further prosecuting Shaw for the Kennedy’s assassination.

Over 2000 books have been written about the Kennedy assassination, many of them shaping Shaw at the center of a conspiracy that involves everything from the CIA, the FBI, the mafia; President Johnson; pro-Castro Cubans; anti-Castro Cubans and Lee Harvey Oswald assassin, Jack Ruby. Oliver Stone’s film JFK suggests that Clay Shaw was Bertrand Clay, despite evidence to the contrary.

Garrison framed Shaw to boost his own career, according to Fred Litwin, author of On the Trail of Delusion: Jim Garrison—The Great Accuser.

Litwin, who has collected hundreds of documents on the case, believes that all the JFK assassination conspiracies are false and that Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone.

“Why was Shaw targeted? Shaw spoke Spanish, was gay, and had the same first name as the fictitious Clay Bertrand. He was a very good man, and had nothing to do with the assassination,” Litwin told Newsweek.

Getty Images

“Shaw was forced to sell his house on Dauphine [Street] and move into smaller quarters. He was fortunate that his lawyers charged him little but he had to pay about $50,000 in investigative fees,” Litwin said. “There was no discovery in Louisiana courts at the time, and so his lawyers had to hire detectives to run down every lead that appeared in the newspapers.”

“Garrison ruined his life, and Shaw died before his damages lawsuit could be heard. I think an apology is needed,” Litwin added.

Newsweek emailed the New Orleans District Attorney’s office on Saturday and Tuesday to ask if the office would apologize to Shaw.

Fred Litwin

Anthony Summers, an author who believes that Kennedy was the victim of a conspiracy, agrees that Shaw was unfairly treated and that his trial was “a travesty.”

“I looked into the Clay Shaw trial while working on my book Not in Your Lifetime. My interviewees included former New Orleans DA Jim Garrison, whom I judged a dubious character. I concluded, too, that the Clay Shaw trial was a travesty of justice.”

“Oliver Stone’s movie JFK, drawing on Garrison’s work, irresponsibly muddied the ground in a case that was and remains important to the nation,” Summers told Newsweek.

“I, in fact, agree with Fred Litwin’s view of Garrison and the trial. Whether Shaw should receive a posthumous apology, however, is a matter for the New Orleans authorities,” he said.

A Gallup poll published on Monday shows that the majority of Americans believe that Lee Harvey Oswald did not act alone, although that percentage has dropped significantly in the last 20 years.

“The 65% of U.S. adults who think Oswald worked in concert with others and the 29% who say he was solely responsible are roughly in line with the previous readings from 10 years ago. Belief in a conspiracy was higher between 1976 and 2003,” Gallup said in a statement.

Gallup said that from the mid-1970s through the early 2000s, Americans’ belief in a conspiracy ranged from 74 percent to 81 percent, before it declined in the two most recent polls, conducted on the 50th and 60th anniversaries of the assassination.

Newsweek sought email comment on Wednesday from director Oliver Stone.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Source link